Boston's Missing Mountains: How We Built the City

Our Boston Hidden Gems Logo is an interesting choice. There aren’t images of skyscrapers, cityscapes, or revolutionary iconography. Why are there mountains? This seemingly simple design hides a dramatic story of transformation and engineering in Boston’s past.

Boston Hidden Gems Logo

Our company logo represents the Tremont, which were the "three mountains" that once defined the northwest corner of the Shawmut peninsula, where Boston now stands. These peaks, which were more like large hills than full mountains, were the original skyline. This cluster gave the area its original French name: Trimountain.

When visiting Boston today, you might wonder: Where are these hills?

The landscape is dramatically different. Workers famously leveled two of those hills and used the earth to fill in the nearby mud flats, creating the elegant Back Bay neighborhood we know today. This project was one of the most significant land reclamation efforts in history. But the destruction of those two hills wasn't just about making new land; it profoundly shaped the identity and layout of modern Boston.

Only Beacon Hill remains. Although workers reduced its height, it still features the beautiful, steep cobblestone streets and traditional 1800s-style homes that give Boston its charm, including the iconic Massachusetts State House.

The story of how Boston lost its mountains is key to understanding the city as it is today.

The Transformation of Trimountain

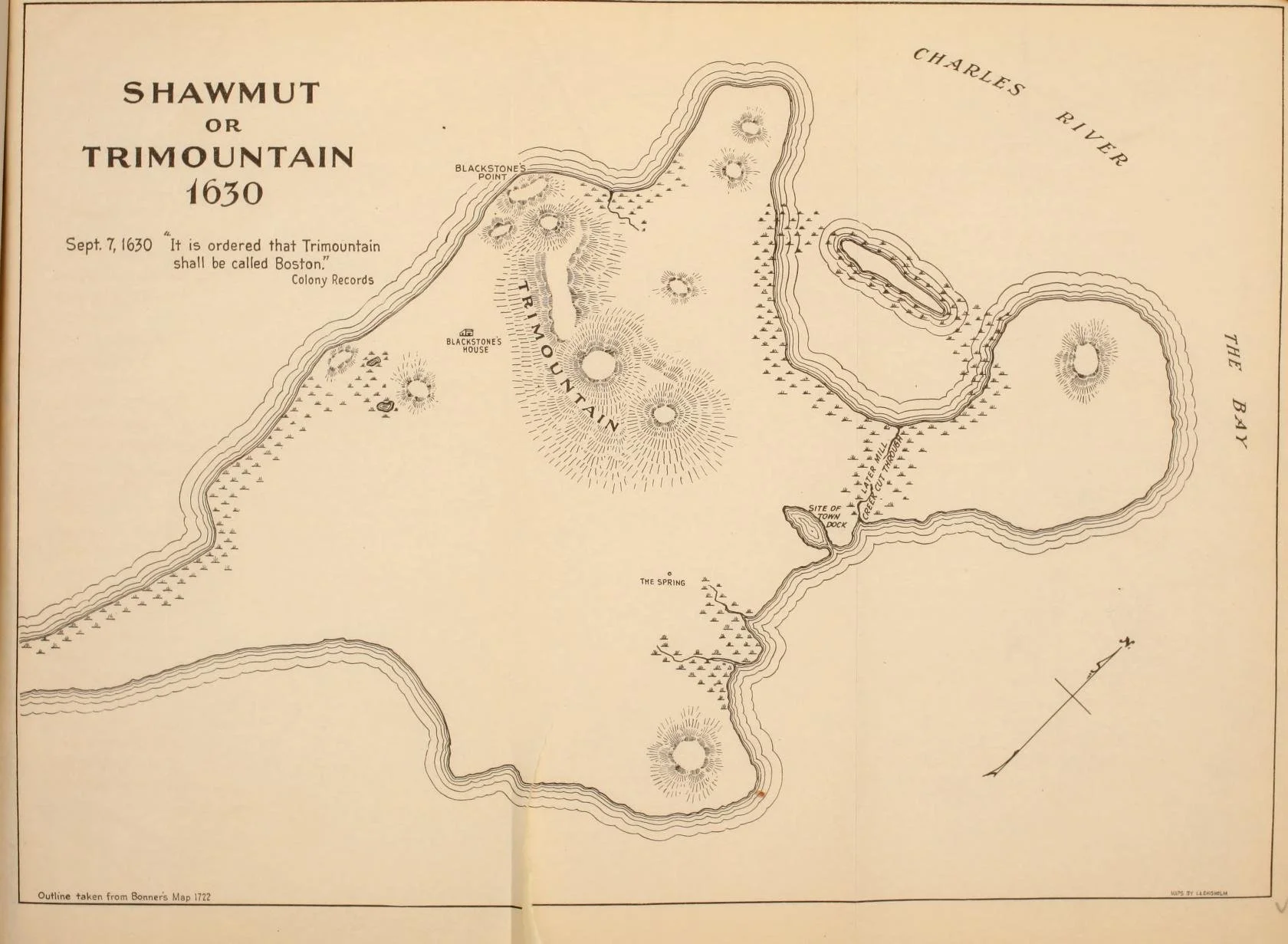

Map of the Boston ‘Shawmut’ Peninsula with the Trimountain

Before explorers and settlers set foot in North America, the land was cared for by Native Americans. The landmass that is now Boston was home to the Massachusett and Wampanoag tribes. Historically known as the Shawmut peninsula, this name derives from the Massachusett-Algonquian word Mashauwomuk. Scholars debate its meaning, but the strongest interpretations suggest "the canoe landing place" or "a fountain of living waters," both of which highlight the peninsula's importance as a strategic water resource and travel hub.

The original landmass and natural bedrock included a cluster of three large hills or ‘mountains’ on the western part of the Shawmut peninsula. When English and European settlers arrived in the 1630s, they named the mountain the Trimountain after its three prominent peaks. Residents later shortened the name to Tremont and eventually called the hills Beacon Hill, Mount Vernon, and Mount Pemberton. Today, only Beacon Hill remains as a namesake of the original Trimountain group.

When visiting Boston today, you might wonder: Where are these hills today?

Settling Boston (1600-1700s)

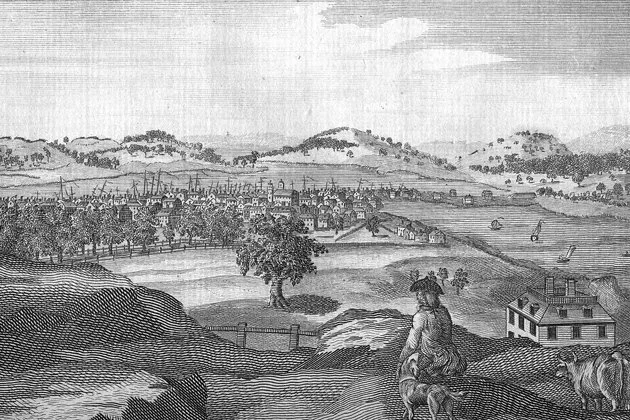

View of Trimountain, Boston 1700s

As the City of Boston was taking shape, the Trimountains were serving a variety of purposes.

The prominent central hill of the Trimountain received its permanent name, Beacon Hill, after English settlers constructed a towering wooden signal there in 1635. Its purpose was to alert the entire region to threats, whether from attack or epidemic outbreak. Settlers never used the beacon, and eventually they removed it. But still, the Beacon name lives on.

Shortly after the founding of Boston in 1630, Puritans launched the North Cove Dam project. In July of 1643, the town granted the land to a group of proprietors to erect a grist mill powered by the tide in the north cove. This tide mill would be essential to grind grain (grist mills) and cut lumber (sawmills) powered by the tide in the north cove. The dam reached from the back of the Trimountain all the way to the North End of the peninsula.

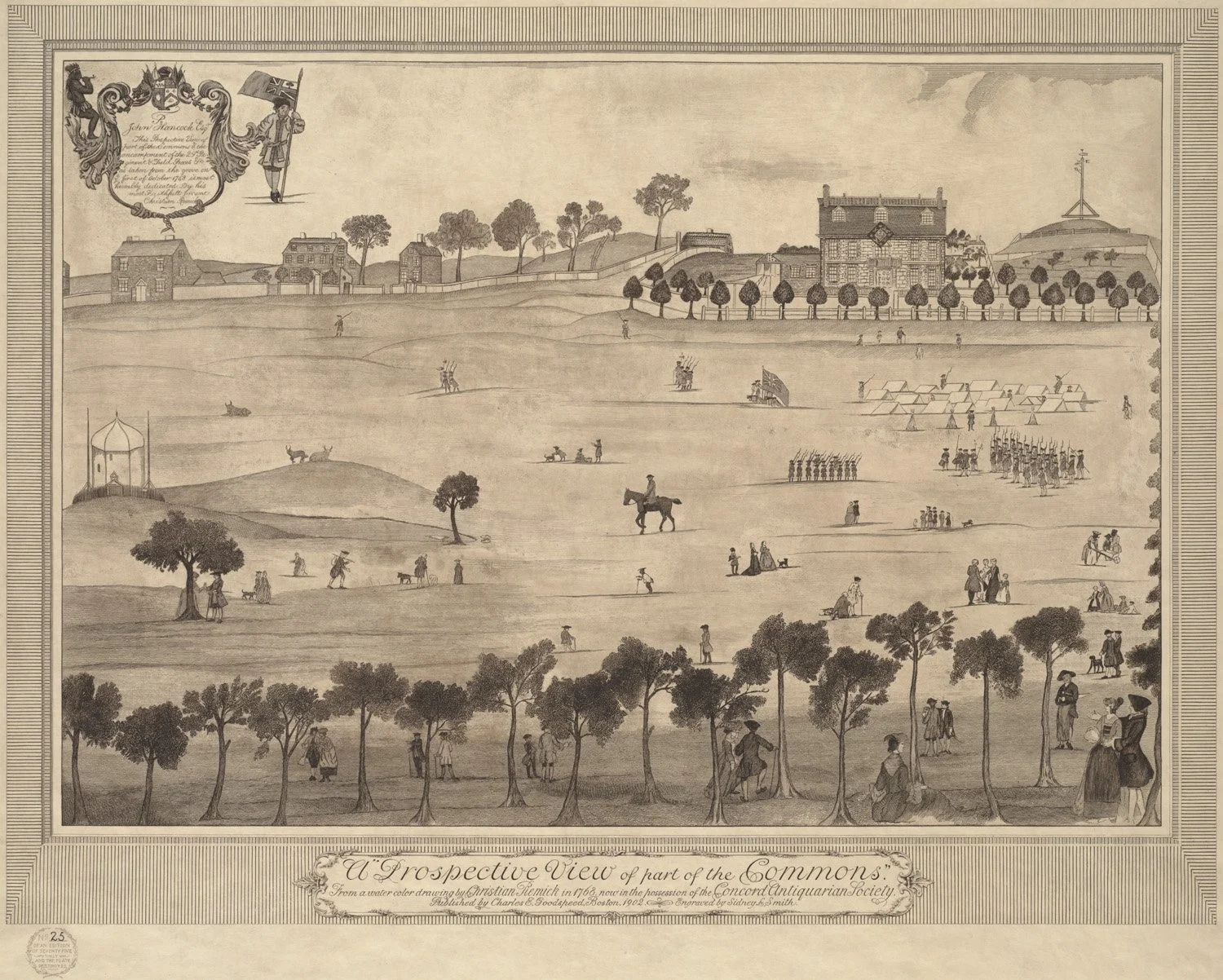

On the other side of the peaks, closer to downtown, the Trimountain hosted Boston Common, a public park. Citizens of Boston used the hills and land as pasturelands for livestock and cattle to graze. This identity would evolve in the early 1700s, when the hill became a coveted site for Boston's wealthy and elite to build.

The first house to be built on the slopes of the Trimountain was the Hancock Manor. Constructed between 1734 and 1737, the Manor was for the wealthy merchant Thomas Hancock (1703–1764). This home was the pioneering structure on the western slope of Beacon Hill. It stood completely alone without any neighbors until approximately 1768, when the portraitist John Singleton Copley built a house farther down the hill.

Boston Common - 1798

Thomas Hancock could afford such a manor because he was one of the wealthiest men in Boston. Starting as an apprentice and indentured servant to a bookseller, he later owned his own bookshop. He became an influential overseas merchant and businessman. Although his own achievements significantly contributed to colonial commerce, he is best known as the uncle and benefactor of the famous revolutionary, Son of Liberty, and patriot, John Hancock.

In the 1800s, the Trimountain underwent significant alterations that facilitated the further development of neighborhoods and habitable land.

Industry & Evolution (1800s)

Massachusetts State House

In the 1800s, as our nation was taking shape with its own identity, industry and innovation were ramping up. The previous centuries of urban development resulted in space scarcity in the city and a need to transform the urban landscape. With new technologies like steam-powered railroads, their infrastructure enabled large-scale projects in the towns across the country, including Boston. The 19th and 20th centuries were a period of major land reclamation projects, which doubled Boston's size.

A key component of the transformation of the Trimountain would be the need and desire for a new capital building in Boston. John Hancock sold the land near the Hancock Manor atop the Boston Common to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to make space for the modern-day State House (1795–98). The cornerstone was laid in 1795 by Governor Samuel Adams, and the central structure of the State House was designed by Charles Bulfinch (1763–1844), who was a highly influential Boston architect. Initially, the eye-catching dome was made of wood, but in 1802 it was covered with copper supplied by the Revere Copper Company, owned by Paul Revere. The dome was later gilded with gold in 1874.

Mount Vernon

The State House spurred residential development in the surrounding area. Charles Bulfinch was integral in designing and planning much of the Beacon Hill district, including the leveling of Mount Vernon. As the architect and planner of this new district, he would repurpose the upland pastures of the Boston Common. He played a prominent role in transforming the area into a desirable residential neighborhood for wealthy Bostonians. The southern slope (nearest the Common) was carefully planned as an upscale residential area for the elite who were leaving denser regions like the North End. Many buildings in this neighborhood are inspired by 1800s Federal-style architecture and free-standing mansions. The Southern Slope "became the seat of Boston wealth and power."

In 1799, Mount Vernon Hill, the westernmost hill, was excavated and ultimately leveled. A suspected reason for this hill’s demise is its unpleasant reputation; this western hill had been known as ‘Mount Whoredom’ for the variety of criminal and scandalous activities that took place there. Sailors, British soldiers, and others often visited the area for activities deemed inappropriate. Despite this negative reputation, the north slope became a vibrant, diverse, and working-class neighborhood. It was home to many people, including sailors, African Americans, and immigrants arriving from Eastern and Southern Europe.

Gaining traction, the land leveling effort ramped up in 1803, in which the soil and gravel from the hill were deposited in the nearby tidal mudflats along the Charles River. The goal of this project was to develop the Beacon Hill slope into a new neighborhood under the design of Charles Bulfinch. Mount Vernon would become the bustling shopping street known as Charles Street. From its disreputable history to the prestigious neighborhood that it is today, this transformation was only the beginning.

Beacon Hill

In 1807, Beacon Hill was reduced from 138 feet in elevation to 80 feet by workers using shovels and horse-drawn carts to move the dirt, rocks, and gravel from the hills to the pond. The previously valuable energy source for mills had become a problem. The Mill Pond, after more than a century of use, had become stagnant, smelly, and unhygienic. The solution was to fill the pond and fill out the landmass between the Trimountain and North End. This project began in 1807 and was completed in 1828, when 50 acres of new man-made land were created that today includes Bulfinch Triangle and the TD Garden/North Station complex.

Leveling Beacon Hill

Mount Pemberton, Railroads, & Back Bay

As the city created land for residential or business development, a new technology became a source of excitement and opportunity: the Steam-Powered Engine. Trains greatly enhanced the city’s ability to transport raw materials, such as rock and soil, to fill the coves surrounding Boston. By the 1830s, it was deemed more profitable to fill the coves and wharves to build railroads than to keep them open for shipping. Specifically, in 1835, the Boston & Lowell Railroad Company leveled Pemberton Hill to obtain fill for laying tracks and creating land for its terminal, where North Station is located today.

Down came Mount Pemberton to make way for new train lines and public transportation. Once leveled and complete with train lines, the railroad cars began filling the 700 acres of the bay in 1857.

For decades, the filling project was fueled by an immense effort: 3,500 railroad cars of gravel were delivered daily, day and night, from Needham and other distant areas. When the Great Fire of 1872 swept through Boston, destroying much of the city, the rubble was incorporated into the Back Bay landfilling effort. When the project finally ended in 1882, the new land nearly doubled the size of the Boston peninsula.

The newly built area became the Back Bay neighborhood, with houses subject to uniform height and weight limits. This neighborhood bears a striking resemblance to London, with its Gilded Age brownstones, and to Paris, with its wide boulevards, complete with a central green space in the middle for statues and benches.

Back Bay dock into the Charles River, 1828

Where we are today

The entire process of leveling the trimountain hills and filling coves spanned nearly 100 years. Today, the land-filled areas are virtually indistinguishable from the original Shawmut peninsula, and Boston is simply a wide, relatively flat city.

This massive project fundamentally transformed Boston. While it eliminated the smelly, unsightly coves and stagnant dams created by the city, it also destroyed the natural wetland ecosystem that had existed there. Although such a project would be impossible under modern environmental regulations, this transformation was considered a great boon to the community, allowing the city to grow and prosper.

The three major peaks on the Shawmut Peninsula have contributed significantly to the settlers and to the modern people who live in and visit Boston. So now you know about the three hills of Boston. And if you know where to walk, you can walk the cobblestone streets of Beacon Hill, walk across Mount Vernon and shop on Charles Street, and explore Mount Pemberton through beautiful Back Bay. Three peaks with far less elevation!